TEATRO DEL LAGO

FRUTILLAR, CHILE

10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY CONCERT

Introduction:

This performance will feature composers ranging from the eighteenth century and the twentieth century, and timeless pieces that seem to be foreshadowing later stylistic techniques. Ludwig van Beethoven, Béla Bartók, and Dmitri Shostakovich are all composers that have created renowned quartets that have shaken the musical world. Dmitri Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8 brings forth elements from his own previous compositions, such as symphonies, opera’s, and concerto’s that symbolize key points in his personal life that have been reflected in his music. This quartet ranges through a spectrum of emotions from deep distress to optimism and joy. Béla Bartók, often considered as the father of ethnomusicology, composed his String Quartet No. 5 using styles from both Bulgarian folk music and Beethovian techniques. The Scherzo movement displays rhythmic techniques used as a bridge between folk and national styles of music, and his own techniques as a composer. Ludwig van Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 Op. 131 is considered to be one of his greatest works, the fourth of the five late string quartets. In this quartet, Beethoven alludes to themes from all movements alike, creating connections between them, and successfully brings the quartet full circle. At first glance, these composers and their pieces may seem to have no relationship at all, but when one hears closely and attentively, all the connections come together in the mind.

String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Eighth Quartet was composed in three days, following his tour of the bombed-out ruins of Dresden, Germany. During this tour, Shostakovich came to reevaluate the meaning of life, and stated in a letter to a friend, “I started thinking that If some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory for me, so I had better write one myself”1. He proceeded to write a dedication in the Quartet, “to the memory of the composer of this quartet”2, and used a motive in the piece that symbolized his musical signature, DSCH, which translated to German note names, is D – E♭- C – B. This motive is set in motion by the cello at the very beginning of the piece, and subsequently appears at different times in the later movements. This motive also evokes themes from Ludwig van Beethoven’s late String Quartet No. 14 Opus. 131, which is the last quartet that will be played in this concert.

Each movement in the quartet features musical representations of different points in his life. Some optimistic and some that are borderline tear-jerking, as he was experiencing a tumultuous relationship within the culture and politics of the Soviet Union.

The quartet includes multiple references to other composers’ styles and works, as well as some of Shostakovich’s own previous pieces. Some of the allusions of his past pieces include Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1932), The First Symphony (1925), The Eighth Symphony (1943), The Second Piano Trio (1944), The Cello Concert (1959). Works from different composers were also alluded to, such as Wagner’s The Funeral March from Götterdämmerung (1876), Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony First Movement (1893), and The Revolutionary song Tormented by Grievous Bondage.

The quartet begins with a Largo movement, which is slow and contrapuntal. It is also said that the second and third movements display the optimism and hopefulness that Shostakovich was living at the time. However, these movements display these feelings in rhythm and structure, not in tone. The second and third movements possess a scherzo-like rhythm, but are partnered with a despondent and anxious tone. The third movement itself begins with a harsh and resonating DSCH motive, played by the first violin. This dramatic beginning is followed by the scherzo-like rhythm, similar structure to the second movement. However, this tone is much more sinister and on edge than the second movement. The fourth movement of the quartet includes references from one of Shostakovich’s opera’s, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1932), more specifically ‘Katerina’s’ lovesick aria. This is anticipated by an extense quotation from The Revolutionary song Tormented by Grievous Bondage. ‘The movement ends with a return of the terrifying music with which it begins, a strained stillness interrupted by sudden, sharp, repeated chords heard by some as the ominous pounding on the door in the middle of the night, when the Soviet authorities came to take someone away.’4

Béla Bartók and Ludwig van Beethoven primarily brought different themes and techniques of other composers and styles, different to Shostakovich who for the majority alluded to his own past works. Dmitri Shostakovich seems to have composed a self-written obituary, bringing in both tragic and hopeful aspects of his life into one piece.

“It is a pseudo-tragic quartet, so much so that while I was composing it I shed the same amount of tears as I would have had to pee after half-a-dozen beers. When I got home, I tried a few times to play it through, but always ended up in tears.”

Dmitri Shostakovich 5

Intermission

String Quartet No. 5 in B♭Major, Scherzo.

Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945)

Throughout his years, Béla Bartók came to be acknowledged as one of the most important Hungarian national composers of the twentieth century. Before traveling abroad to perform in Berlin, Paris and Vienna, the gifted pianist, composer and later ethnomusicologist Bartók initially studied at the Budapest Academy of Music. After his extensive travels abroad, he returned to the academy and taught piano in 1906, but then immigrated to the United States in 1940 given the growing alliance between Hungary and Nazi Germany6.

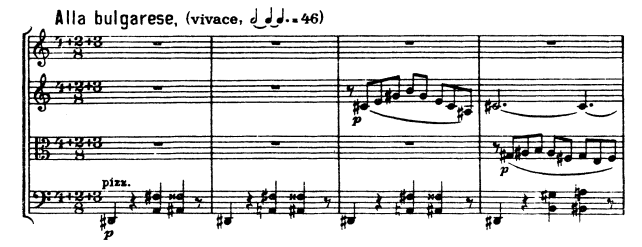

Bartók was deeply invested in the art of folk music, and believed that it was a gateway into a concoction of modern music with styles from his native soil. He publicly criticized other Hungarian composer’s failed attempts to create an authentic national Hungarian style, signaling that the pieces were based on stereotypical Roma-style melodies and also based on non-Hungarian cultures. He shows prominent influence from the unique rhythms of Bulgarian folk music, ‘with meters made up of irregular groupings of two and three beats, as reflected in the 4+2+3 over 8 time signature in the Fifth String Quartet’7 (Figure 2). These rhythmic techniques are combined with metrical conflict, a style made famous by Ludwig van Beethoven. Similar to Beethoven, Bartók presents themes in the first movement that are revisited in the finale, not presented in this performance. However, in the Scherzo, the groupings and placements of dissonance that are presented at the start of the movement are revisited again. Bartók used these rhythmic influences as a bridge between folk and national styles of music, and his own techniques as a composer. To further accentuate this, Bartók inserts a rhythmic indication at the beginning of the Scherzo Movement ‘Alla bulgarese’, meaning ‘In a Bulgarian style’.

Dissonance is something that never ceases to surprise in Bártok’s works. The starting theme seen in Figure 2 is just one of the many instances where the motive is repeated through dissonant variations. The cello seems to follow the shape of a stereotypical tonic-dominant alteration, but has some irregularities. It goes from a D♯to an A (a tritone away) and then there is an A♯as the lowest notes in the patterns. The short arpeggiated theme Figure 2 is answered by a lively, irregular dance melody. In the middle of the movement, the arpeggiated theme is intervallically modified, becoming a high ostinato on the violin, while a simple tune is sounded alternately by the other instruments. Throughout the entire Scherzo, in addition to the metrical conflicts, there is significant rhythmic uniqueness originated from Bulgarian musical techniques. There are various times throughout the piece where the phrasing and stepwise notes, such as shown in measure 3, is repeated chaotically by all of the instruments at different times, creating a prominent polyphony. This is Bártok combining Bulgarian folk rhythmic techniques into his own stylistic influences from Beethoven, such as some ‘country-dance tunes’. Bartók is successfully showing how folk music is now part of his ‘mother tongue’ and successfully integrating it with traditional music techniques.

‘The implication that a mother tongue is not something you are born with but something you have to master is a stark reminder of the challenges composers faced during these years in forging a sense of identity and wholeness’9.

String Quartet No. 14 in C♯minor, Opus 131.

Presto; Adagio quasi un poco andante; Allegro

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

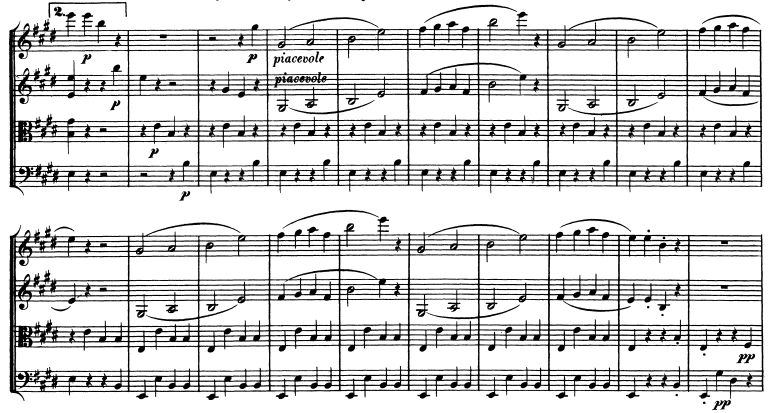

The C♯minor quartet is the fourth of Beethoven’s five late string quartets. This quartet was composed the year before Beethoven’s death, and is also considered to be one of his greatest works. Similar to Bartók’s String Quartet No. 5 and Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8, Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 is a multi movement piece. The whole quartet possesses striking contrasts of style and feeling within the seven movements, but show a full circle when themes from the first movement are revisited in the finale. This performance will delve into the last three movements, (V) Presto, (VI) Adagio quasi un poco andante, (VII) Allegro. The Presto movement is an exuberant scherzo starting in E Major, the relative minor of C# minor. The slower, more legato theme of the Presto movement is originally presented in E Major, and seems to work as an outline for the fast paced cut-time quarter notes to work around. An ironic technique, similar to Shostakovich’s way of distributing themes. This is played by the first violin in the higher octave, and the second violin an octave lower (Figure 3).

Following the styles that many have mimicked, Beethoven revisits this theme later in the movement, but with a key change variation. The third and fourth movements of the quartet are in D major and A major, respectively. The theme of the Presto is revisited in these keys later in the movement, which actively shows the continuity of the piece. The sixth movement, Adagio quasi un poco andante, is a short and somber movement, which serves as a type of introduction into the final movement, the Allegro. The final movement begins with a remarkable ruthlessness, ‘the finale burgeons with country-dance tunes, of a kind associated in the other late quartets with the interior dance movements’11. This shows yet another contrast with the supreme seriousness of the opening of the C♯minor: an antique fugue. Resemblances to the ‘country-dance tunes’ can be heard in Bartók’s String Quartet No. 5 Scherzo, and in some aspects of Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8. This last movement is a combination and recapitulation of all the previous movements, especially themes from the first movement, Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo. It also includes references to different motifs in different keys, from the previous middle movements. Because of this, the Allegro emits a constant feeling of uncertainty, not fully knowing where the piece is resolving. The crucial partnership between the first and final movement shows how the seven movements come back together as a final circle. However, when the Allegro ends on the final cadence in C# Major, it feels as if there is more to come. Beethoven leaves the listeners wanting more. Considering that he composed his greatest works the year before he died, and that the quartet possesses such intensity and dramaticism, it is impossible not to wonder what was going inside Beethoven’s mind at this time.

Works Cited

Auner, Joseph. Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. 67-184. New York; London: W.W. Norton and Company, 2013.

Bártok, Béla. String Quartet No. 5, Scherzo, 33. Vienna: Universal Edition, 1936. Reissue – London: Boosey & Hawkes, 1939.

Beethoven, Ludwig van. String Quartet No. 14, Opus 131, Presto, 139. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1863.

Grove Music Online. Beethoven, Ludwig van. Retrieved December 17, 2020. Kerman, J., Tyson, A., Burnham, S., Johnson, D., & Drabkin, W. (2001).