Towards the beginning of the twentieth century, composers started to actively choose to move beyond and break away from the Post-Romantic idiom, and make room for new musical possibilities, such as Expressionism. Alban Berg (1885-1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School, founded by Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951). While we often think of Romanticism and Expressionism as opposed, and thus of musical history as a series of discrete ‘periods’, in fact there are always continuities despite absolute breaks. Berg was part of both Expressionism and Romanticism, and therefore is neither the cause nor the effect of the transition from one to the other. This change was not a passive process, but rather an active one. Composers felt the need to break away from Romanticism, into something completely different, that the public most definitely did not accept completely. This new musical era opened new possibilities in music creation, such as integrating connections with the past, and even variously manifesting these connections via allusions to older forms, techniques, and even pieces. Berg’s Violin Concerto of 1935 is the perfect example of his use of romantic lyricism and combination with Schoenberg’s twelve-tone method. The twelve-tone method was the culminating break from the Romantic period, a direct result of composers seeking to impose order that gave meaning to an excess of choice. As stated previously, Berg incorporates older forms and sounds into his twelve-tone works, through elaborate compositional devices. Alban Berg alluded to traditional schemes of tonality, form and expression through the use of themes and variations based on previous musical traditions to produce a positive ambiguity out of the same tonal and atonal contradictions that Schoenberg and his pupils faced.

Alban Berg openly criticized the backlash that Expressionism music often received. He released a statement of aims entitled Society for Private Music Performances in Vienna (1919). The society was founded by Arnold Schoenberg in Vienna in 1918, with the objective of separating twentieth-century music from concert culture and life, as well as from the musical public as a whole. In the statement, Berg critiques the way expressionist music is perceived by the public, as the works are “therefore valued, considered, judged, and lauded, or else misjudged, attacked, and rejected, exclusively upon the basis of one effect which all convey equally ー that of obscurity”1. He also states how it not only affects the composers and the production of music itself, but also anyone who’s opinion is ‘worthy of consideration’. There is a recurring theme of alienation that is thrusted upon these modernist composers and their pieces, which roots from the public’s lack of understanding of the music itself, which they then associate with discomfort and unpleasantness. These composers now seek to avoid public scrutiny, and mark the idea of approval as irrelevant. Berg additionally states that through the achievement of “preparation and frequent repetition”2, the obscurity is replaced by clarity which only then can an “audience establish an attitude towards a modern work that bears any relation to its composers intention”3. Given Berg’s suggestion that these new pieces were of necessity unfamiliar and even difficult, it’s surprising to discover that some of his music is nevertheless filled with familiar forms, sounds, and procedures. His Violin Concerto of 1935 offers a remarkable combination of new and old, including twelve-tone rows, Baroque forms, allusions to familiar-sounding tonal patterns, and even a quotation from one of Bach’s most celebrated chorale harmonizations.

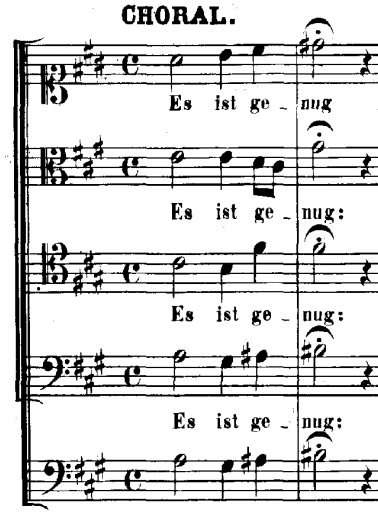

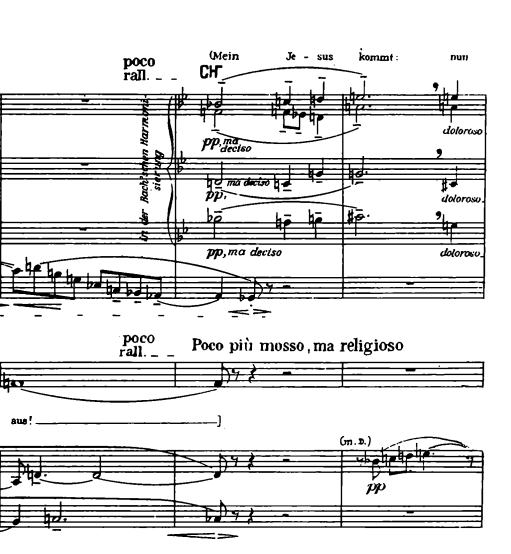

The second movement of the Violin Concerto, Berg integrates phrases and harmonies from the very famous Bach Chorale “Est ist genug” from the Cantata No. 60. Berg rearranges the chorale into a twelve-tone composition, and uses the original harmonization in different parts of the piece, joining the new with the old. The integration The integration of the Chorale comes at a time of heavy climax composed by a harsh mixture of sounds. As these sounds subside, we can start to hear subtle hints of the four note phrase of the chorale being played by the woodwinds, gradually becoming more distinct. This is also accompanied by the Bach harmony itself. The whole process is very interesting, as Berg alludes to a renown chorale phrase and harmony from an older time, as if he were reaching into the listener’s comfort and showing it in a different context. One could try to imagine how it would be to listen to this piece at the Society for Private Music Performances in Vienna, listening to Berg’s subtleties through the woodwinds and moving us closer and closer to the message he is trying to convey. Berg uses these techniques in order to transition the public into new music, while still respecting and using older music. It is as if Berg is trying to tell us something through these techniques; perhaps that Bach is quite modern, or that Berg himself isn’t as modern as he seems to be?

As mentioned before, Berg alludes to this chorale and harmony style through the woodwinds, and we can now see in Figure 2, where the Bach chorale is showcased in plain sight. What is also quite interesting, is that the fragment is in fact a segment of a Whole Tone scale, which brings to question whether Berg is telling us that in reality Bach was modern, or that Berg himself was not as radical as the public thought. Berg uses the Bach chorale as a way to allude to traditional forms of harmony and themes, subsequently producing positive ambiguity out of the same tonal and atonal contradictions that Schoenberg both produced and was criticized for. The use of variations of traditional forms of harmony and melodies creates a mild sense of comfort for the listeners. As Berg clearly states in his statement of aims, composers are subject to ridicule, mis judgement and rejection solely because their music is ‘obscure’. This particular passage (Fig. 2) is in the midst of a very tumultuous and possibly ‘uncomfortable’ composition; Berg cleverly incorporates the Bach chorale subtly, as if opening a window into the traditional and comfortable style of music. The chorale is then repeated more and more, until the solo violin plays it as a theme. The use of the chorale seems to work as a breath of fresh air for the traditionally coddled ears of the public, possibly because it takes them back to a time of musical comfort and conformity.

Bernstein’s wonderful analysis then shows a totally unexpected event in a twelve-tone work, which is that the same Bach Chorale is then repeated again. The Chorale is repeated by four clarinets, in pure B♭Major “Bachian” harmony. Bernstein also emphasizes the adjective of “pure” which can be inferred as untouched and not modified in any way, keeping the chorale itself intact. The clarinets play for three whole phrases, and then the violin plays in dissonant counterpoint, and the clarinets subsequently answer with the “Bachian” harmony. The unexpectedness of this whole process is what makes this incredibly interesting. The way Berg uses themes and variations of the Bach Chorale shows the very intentional integration of the old in the new.

Berg differs from Schoenberg and his other pupils, as he succeeds in producing this positive ambiguity, despite the same tonal and atonal challenges his peers and mentors faced. The Violin Concerto solves this ever present tonal obscurity in a very satisfying way, through the hints of familiar themes and harmonies. Alban Berg’s twelve tone theme in the first movement of his Violin Concerto was a dodecaphonic series that spelled out a series of triads: minor, augmented, major and diminished. The ‘row’ gives the familiar sounds a new meaning.

This row is based on the opening melody of the Bach Chorale, because the whole pattern is ‘hidden’ in notes 9 – 12 (B, C♯, D, E♭, F) in the row. “In suggesting that Bach’s music is so closely connected to his own, Berg underscores the insistence by the Second Viennese School that their music, as Schoenberg wrote, was a “truly new music, which being based on tradition, is destined to become tradition””8. Is Berg telling us that the familiar can be modern?

The first four notes of the twelve-tone theme correspond to the first notes that are played by the violin in the piece. The last four notes, starting from the B♮, compose the tritone chord. What makes this so intriguing is how there is a clear transition from the romantic style to the expressionist style. The twelve-tone row begins with a series of traditional intervals, and then ends with an outline of the tritone, which is widely considered as atonal and disruptive. Interestingly enough, this piece was dedicated to the memory of Alma Mahler’s daughter, and therefore representing the peaceful acceptance of death9. Berg, however, portrays death as atonal and disruptive, but with these subtleties that make it peaceful in the end.

In contrast to Schoenberg and his other pupils, Alban Berg uses traditional themes and techniques in his compositions in order to create a positive ambiguity within the twelve-tone method. In Berg’s Violin Concerto, he incorporates themes and variations of the famous Bach Chorale “Es ist genug” from Cantata No. 60, which in turn creates a shift between the expressionist and the traditional aspect of the piece. Berg absorbs tonality within his twelve-tone composition, by using the recurring themes of Bach’s chorale, as a way to familiarize the listeners with techniques that they are and were previously accustomed to. As was mentioned earlier, his suggestion that these new pieces were of necessity unfamiliar and even difficult, it’s surprising to discover that some of Berg’s music is nevertheless filled with familiar forms, sounds, and procedures. Through this, Berg successfully achieves this positive ambiguity, a goal rooted by a genuine obsession with the integration of traditional forms into new and modern music compositions. Berg felt the need for a new foundation of music, and believed similar to Schoenberg, that “truly new music which, being based on tradition, is destined to become tradition.”10

Works Cited

Auner, Joseph. Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. 134-136. New York; London: W.W. Norton and Company, 2013.

Bach, Johann Sebastian. O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort BWV 60, Es ist genug, 22. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1863.

Berg, Alban. “Society for Private Music Performances in Vienna”. In Strunk’s Source Readings in Music History, rev. edn, ed Nicolas Slonimsky, Music Since 1900, 4th ed, 191-192. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971.

Berg, Alban. Violin Concerto, 6. Vienna: Universal Edition, 1936.

Bernstein, Leonard. The Unanswered Question: The Twentieth Century Crisis. PBS, 1976.