Twentieth century composers found themselves at the limit of traditional music norms. Composers found themselves alienated by the laws of traditional music because of their beliefs. Charles E. Ives (1874-1954) was a renowned modernist American composer whose works, for most of his life, were either unknown, unperformed or unpublished. He was a well known insurance specialist by day, and a revolutionary composer by night. Ives didn’t believe in musical restrictions, therefore isolating himself from musical society and its norms. Similarly, Béla Bartók (1881-1945) also believed in breaking away from traditional music conceptions through the use of folk music. The Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist was considered to be one of the founding fathers of ethnomusicology. His extensive appreciation and research on folk music led him to transcribe nearly 10,000 folk melodies into scholarly books1.

Ives and Bartók believed in the use of folk music in their compositions, which then alienated them from traditional musical norms. How did these two different composers in radically different contexts make connections and use what they heard in order to break out of these musical alienations? Both of these composers believed that in order to create music, one must be completely immersed in the environment that they are portraying. Do they create their environments in hopes of getting in touch with something that is authentic to them, to break the alienation?

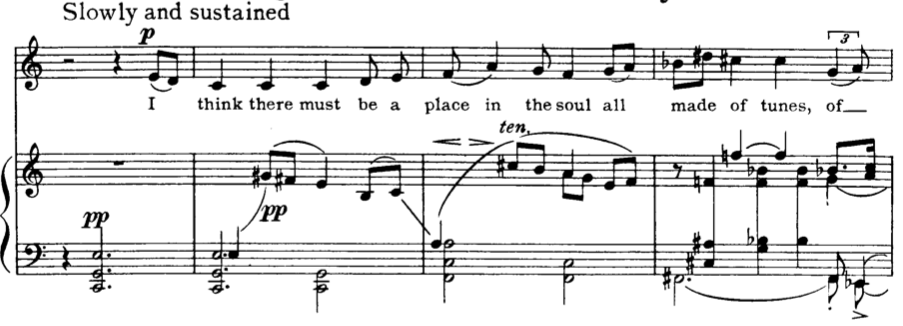

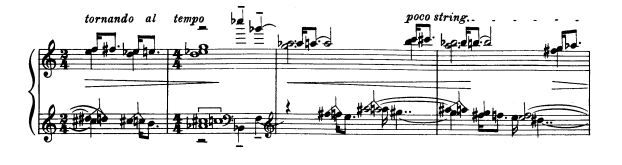

Ives experimented and fused musical contradictions such as “complexity and simplicity, innovation and conservatism, radical experimentation along with quotation of popular tunes and hymns”2. Ives never believed in participating in music conformity, in any shape or form. He was on his own path, setting aside the traditional structures and categories of music. In his music, Ives fused various aspects such as nature and spiritual hymns with popular music, which come together musically as well as bringing into question the importance of physical space and distance. Because of his studies at Yale, he strayed away from traditional music structures and styles, diving in to folk tunes, hymns and marches. These are usually considered traditional, but Ives uses them in ways that make it unorthodox. Different from Bartók, Ives mixes the streams of hymns and marches within his compositions, instead of developing them. The individual streams are traditional, but the structure of the music itself is unconventional. This can be seen in his collection 114 Songs, and more specifically in The Things Our Fathers Loved (Fig. 1).

The vocal section follows its own melody while the piano accompaniment simultaneously follows another. The mixture of hymns creates a dissonance and uncertainty, showing Ives’s ambivalence towards traditional musical structures5. There seems to be a disconnect from melodies that are usually traditional and the way that Ive’s streams them together. In this situation Bartók would have used a different approach, using folk elements and integrating them in his compositions; not making them clash. Additionally, Ives emphasizes spatial effects with the hymns, given that individually they would be perceived differently, but together they create a powerful and intentional effect. Is it possible that maybe the importance Ives gives the distancing of sounds reflects his detachment from society?

Much like Bartók, Ives was trying to get back to something real through the incorporation of folk music in his pieces, as a way to overcome the twentieth century alienation. These composers tried to create an identity within the twentieth century musical movement. In Ives’s mind, ‘real’ is a construct of musical freedom that strays from traditional music laws completely, and is not fueled by external stimulants like money and recognition. In this construct, Ives characterizes music with gender by associating what he believes is genuine to masculinity. He describes rough folk and vernacular music as masculine, and music of urban or cultivated concert music as effeminate. Perhaps this sexist characterization reflects his use of folk music, with the objective of showing the ‘masculine’ authenticity of his career. By characterizing urban/cultivated music as effeminate, he rejects a whole element of modern music, therefore alienating himself as well.

Ives believed that people started getting too comfortable with music and that they started familiarizing beauty with comfort.

Is not beauty in music too often confused with something which lets the ears lie back in an easy-chair? Many sounds that we are used to, do not bother us, and for that reason are we not too easily inclined to call them beautiful?6.

Ives would say that the composers who succumbed to this habitual way of composing must have “been drugged with an overdose of habit-forming sounds”7 that takes away true creativity. In terms of creative expression and lack thereof, Ives believed that the external stimulants harm more than help individual creative work8. Through the commercialization of art, these stimulants take away the true purpose of music creation. Both Ives and Bartók believed in the conservation of peasant and folk music, trying to avoid the commercialization and loss of these tunes over time. Knowing what we know of these composers, this can also be interpreted as a way of conserving music that is genuine to them. Their methods, however different, possess the same desire to protect the genuineness of music and use it to break out of their alienation.

Béla Bartók was constantly open to different styles of music, more specifically Bulgarian folk music, and was heavily criticized by those who believed in national purity. He believed that in order to respectfully and successfully interpret peasant and folk music, a composer must fully immerse themselves into the environment they are trying to portray. In Two Articles on the Influence of Folk Music he constantly criticizes composers like Stravinsky, who would interpret folk music simply from books without means of contextualizing them. He would criticize them because given that they didn’t live or experience folk music, their interpretations weren’t genuine and didn’t respect authentic folk. Ives used folk melodies simply the way they were, joining them in a nontraditional manner. The melodies weren’t themselves distorted, but the way Ives structured them transformed them into dissonance, making his works seem unorthodox. Contrastingly, Bartók believed in learning from folk music, studying it with the objective of using it as a “musical mother tongue”9. He used the methods and techniques of folk music in his works, in efforts to keep folk alive.

Similar to Ives, Bartók also experimented with dissonance, non-harmonic contexts, polytonality, among others. This can be seen especially in his piece “Major Sevenths and Minor Seconds” No. 144 in Volume 6 from his famous Mikrokosmos collection. This piece shows how he uses sharp dissonant combining melodies with similar notes and close intervals. He uses folk music characteristics such as polytonality, chromatic and dissonant harmonies, as well as unorthodox melodies and harmonies10.

Bártok’s objective was to master the forms and techniques of folk and peasant music in order to integrate it in his music subconsciously.

“This implication that a mother tongue is not something you are born with but something you have to master is a stark reminder of the challenges composers faced during these years in forging a sense of identity and wholeness”13.

Like Ives, Bartók was also trying to break out of the twentieth century alienation and trying to forge his identity as a scholar and as a composer. He was doing this by integrating folk elements into his music, keeping the techniques intact, but changing the style of music. It is as if Bartók were trying to create his own environment, where he renovates dissonance and traditional music as a whole. Bartók is trying to get back to something authentic and true to his perception of music. For him, folk music is his perception of authenticity, and is trying to use it to break away from alienation.

Bartók was worried about the distance many composers possessed between the rural contexts of traditional folk music. This is because the folk melodies came to these composers through urban popular forms, or even imitations by other composers. He uses his works to integrate in musical society how folk music should be interpreted: respectfully and mindful of the atmosphere, not just the notes on the page. Bartók believed that folk music was imperative in the composition of works, not just the tunes but the atmosphere itself14. This contrasts to Ives, who used folk tunes as they were, experimenting with the crossing of tunes.

Ives and Bartók both possessed the desire to break out of the alienations of the twentieth century. Knowing what we know about their careers, we interpret that their pieces are a reflection of the difficult times these composers have endured. Both these composers were alienated from traditional music norms, and they approached their desire to break out of it in very different ways. Ives experimented with the crossing of folk tunes and Bartók focused on the study of folk music to then apply the techniques and forms into his own compositions. Despite their radically different cultures and approaches, Ives and Bartók both believed they were in the middle of a disingenuous time, and were both trying to get back to genuine music. They were trying to get back to something authentic to them, which led to them creating their own musical environments which they portrayed in their works.

Works Cited

Auner, Joseph. Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. New York; London: W.W. Norton and Company, 2013.

Bartók, Béla. Major Sevenths and Minor Seconds. With György Sándor. Sony Classical, 2020.

Bartók, Béla. Mikrokosmos, 223-26. New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 1940. https://haverford.nml3.naxosmusiclibrary.com/stream.asp?s=34055%2FHaverford19%2FGJ3749_005

Bartók, Béla. “The Influence of Peasant Music on Modern Folk Music.” In Strunk’s Source Readings in Music History, rev. edn, ed Leo Treitler and Robert P. Morgan, 167-71. New York: W.W. Norton, 1978.

Ives, Charles. “Afterword,” 114 Songs, 261-62. New York: The National Institute of Arts and Letters, 1975.

Ives, Charles. “Music and Its Future”. In Strunk’s Source Readings in Music History, rev. edn, ed Henry Cowell, 65-68. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1961.

Ives, Charles. The Things Our Fathers Loved. With Thomas Hampson and Michael Tilson Thomas. RCA Records, 2002. https://haverford.nml3.naxosmusiclibrary.com/streamw.asp?ver=2.0&s=34055%2FHaverford19%2F3590724

Ives Charles. 114 Songs, 91-92. New York: The National Institute of Arts and Letters, 1975.